Welcome to the

AttachLifter

Minimal invasive access to the pericardial sac with minimized risk of tamponade.

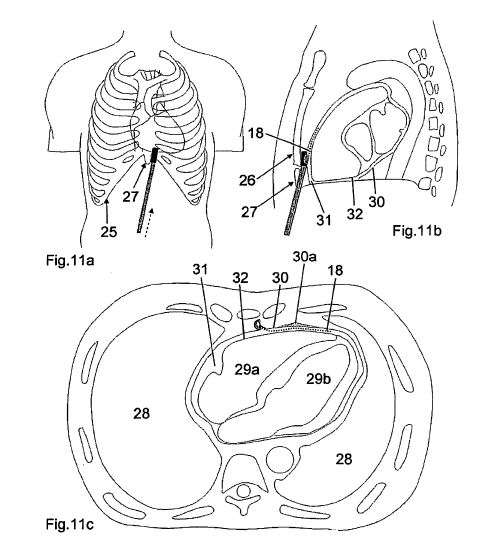

In our minimal invasive approach, the pericardial space can be reached via the subxiphoid procedure. In the context of the conventional pericardiocentesis, the subxiphoid approach is used routinely under local anaesthesia: "Dr. Maisch advocates the use of the subxiphoid approach to the puncture site, which requires fluoroscopy in a cardiac catheterisation suite and involves inserting a needle substernally via the left side of the scapula, at a 30 degree angle to the skin. During pericardiocentesis, the operator intermittently aspirates fluid and injects contrast medium. After aspiration, the needle is quickly replaced with a soft J-tip guidewire. After dilation the guidewire is replaced in turn by a pigtail catheter."

Instead of the needle which obviously cannot be used at all when pericardial effusion is small or absent, the PeriAttacher would be the preferred instrument, since it has a blunt end and cannot injure the heart surface. It minimizes the risk of cardiac tamponade (haemopericardium) present even in large pericardial effusion. Cardiac tamponade is an emergency condition in which blood accumulates in the pericardial sac in which the heart is enclosed. If the blood volume increases, the heart chambers are prevented from filling. This in turn results in depressed pump function. If the blood is not withdrawn in time, shock and death occur. Thus, any progress which minimizes the risk of cardiac tamponade is important.

For further infos: http://www.hipo-online.net

Minimal invasive access to the pericardial sac with minimized risk of tamponade.

From

safe

treatment of pericardial effusion to novel

intrapericardial therapy.

by Rupp et al.

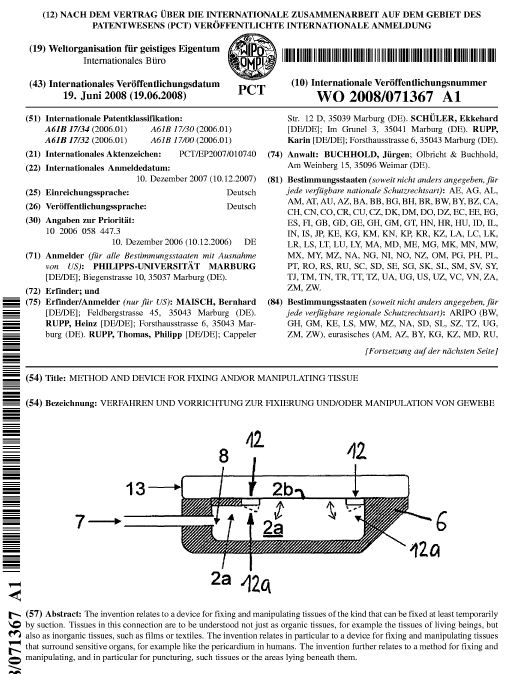

Update 13/12/2011: EU patent on our key technology for minimal invasive pericardial access with the AttachLifter is granted.

Press release by TransMIT

by Rupp et al.

Update 13/12/2011: EU patent on our key technology for minimal invasive pericardial access with the AttachLifter is granted.

Press release by TransMIT

Our

aims:

i. minimal invasive access to the pericardial space with the AttachLifter

ii. safe treatment of pericardial effusion

iii. drug delivery to diseased heart but normal pericardium

i. minimal invasive access to the pericardial space with the AttachLifter

ii. safe treatment of pericardial effusion

iii. drug delivery to diseased heart but normal pericardium

In our minimal invasive approach, the pericardial space can be reached via the subxiphoid procedure. In the context of the conventional pericardiocentesis, the subxiphoid approach is used routinely under local anaesthesia: "Dr. Maisch advocates the use of the subxiphoid approach to the puncture site, which requires fluoroscopy in a cardiac catheterisation suite and involves inserting a needle substernally via the left side of the scapula, at a 30 degree angle to the skin. During pericardiocentesis, the operator intermittently aspirates fluid and injects contrast medium. After aspiration, the needle is quickly replaced with a soft J-tip guidewire. After dilation the guidewire is replaced in turn by a pigtail catheter."

Instead of the needle which obviously cannot be used at all when pericardial effusion is small or absent, the PeriAttacher would be the preferred instrument, since it has a blunt end and cannot injure the heart surface. It minimizes the risk of cardiac tamponade (haemopericardium) present even in large pericardial effusion. Cardiac tamponade is an emergency condition in which blood accumulates in the pericardial sac in which the heart is enclosed. If the blood volume increases, the heart chambers are prevented from filling. This in turn results in depressed pump function. If the blood is not withdrawn in time, shock and death occur. Thus, any progress which minimizes the risk of cardiac tamponade is important.

| Key

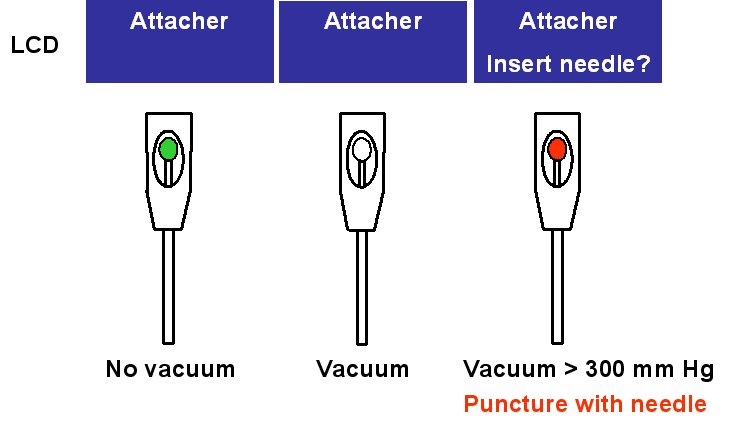

terms: Attacher: our devices with the term "attach" are characterized by the controlled attachment of the tissue to an instrument during a particular procedure, e.g. attachment to the pericardium. When tissue attachment is lost for whatever reason, this is recognized and the procedure is stopped until the surgeon regains tissue attachment. Since "attacher" is a common name, sometimes the prefix "Marburg" is used (the devices were developed at the Philipps University of Marburg). PeriAttacher: a device for puncturing the pericardium, thereby entering the pericardial sac or space. AttachLifter: a follow-up of the PeriAttacher which fails in the case of thickened (due to fat deposition or fibrosis) pericardium. The device uses a novel procedure for entering the pericardial space. |

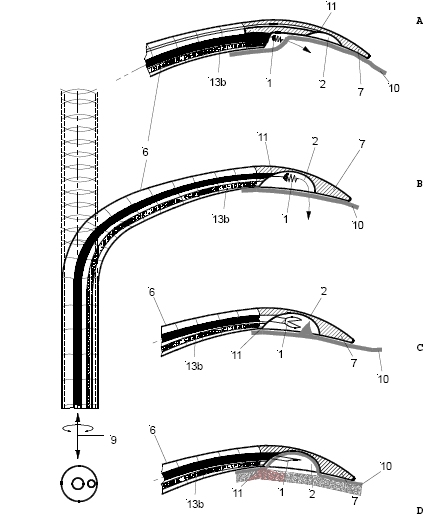

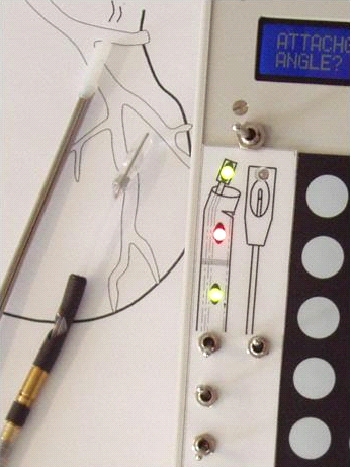

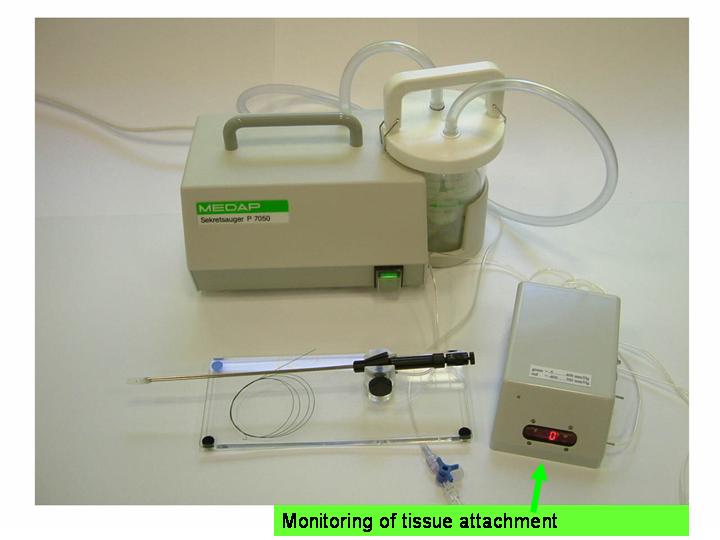

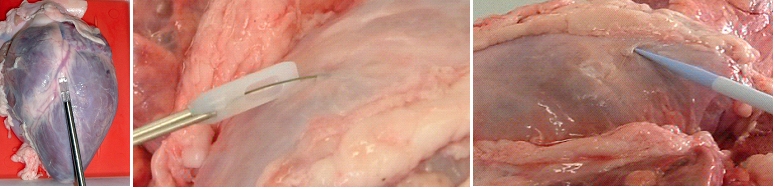

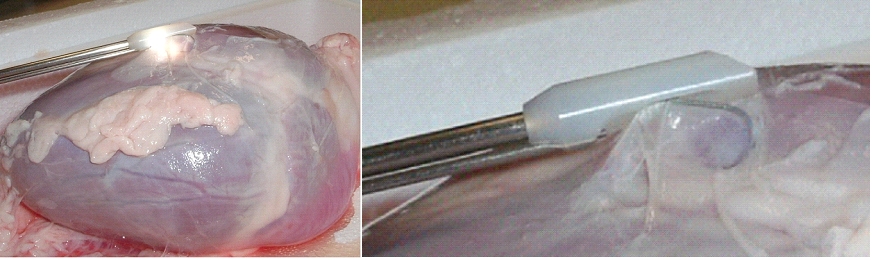

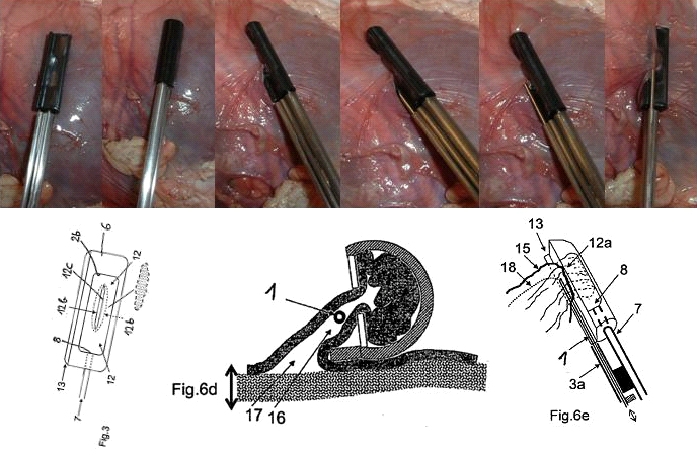

The setup required is simple and requires a regular suction pump, a control console for monitoring tissue attachment and the PeriAttacher (please note, the device shown is an early prototype not suitable for thickened fatty pericardium).  The principal steps of accessing the pericardial sac involve (in the picture below from left to right): Attachment of the pericardium to the PeriAttacher and puncture of the pericardium with a needle (left), introduction of a guide wire located in the needle used in the puncturing step (middle) and dilation of the opening using dilators with successively increasing diameter (right). When the opening is large enough, other instruments can be introduced into the pericardial space, e.g. an endoscope for taking diagnostic biopsies, and drugs can be instilled.  In view

of the many unresolved technical problems, we

addressed at first the

question whether a minimal invasive access to

the pericardium can

indeed be achieved. For accessing the

pericardial sac with effusion, a

system referred to as "PerDUCER" has already

been developed by

Comedicus Inc. The device involves manual

suction with a syringe for

attaching the pericardium to the head piece

prior to puncture with a

needle. Although this procedure has been

validated in pigs, it was less

successful in patients. In

a

study performed by Prof. B. Maisch at the

Department of

Cardiology, Philipps University of Marburg a

successful puncture of the

pericardium with access to the pericardial sac

was achieved in 2 out of

6 patients. This failure rate might not be

unexpected taking into

account that the attachment to the pericardium

was achieved only by

manual suction with a syringe and that in

parallel to the suction, the

needle had to advanced for puncturing the

attached pericardium. Any

loss of attachment is expected to result in

failure of pericardial

puncture. Also thickened pericardium would fill

out the suction head

and the needle would thus not enter the

pericardial space.

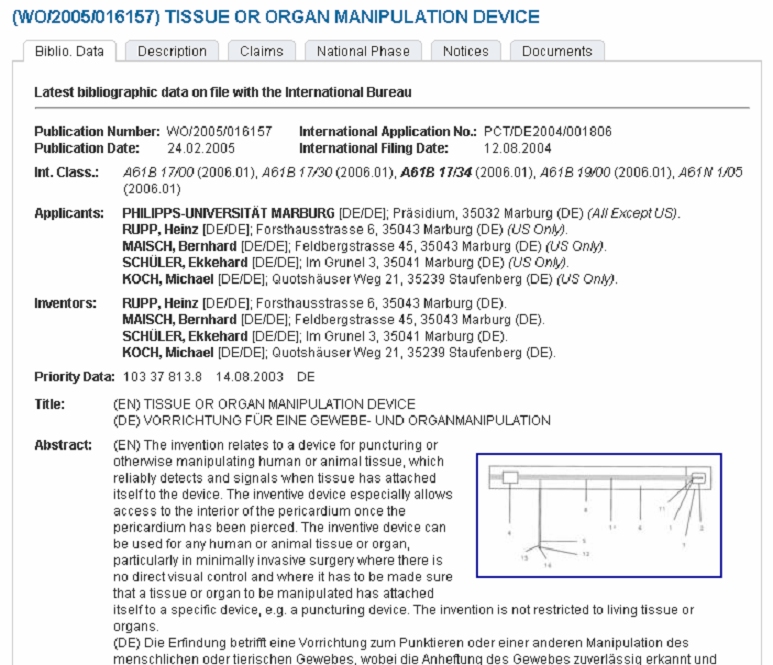

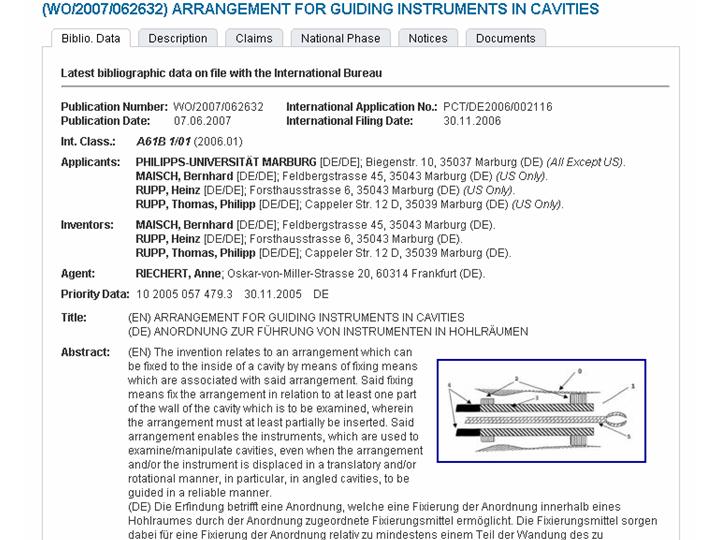

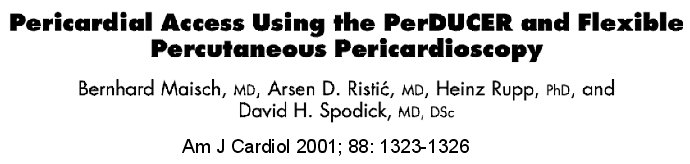

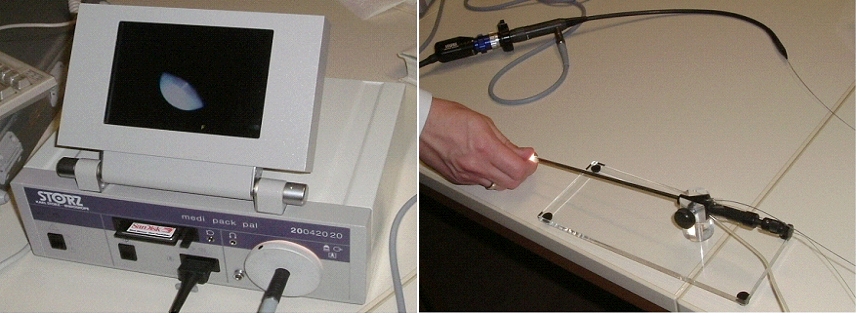

How to develop devices for a minimal invasive access to the pericardial space? A prototype of the "Marburg Attacher” for puncturing the pericardial sac (named PeriAttacher for this purpose) is shown below. A fiberscope was attached which could be used for inspecting the tissue before puncturing the pericardium (picture taken during demonstration of the “11284A Vaskular-Fiberskop” of Karl-Storz Endoscopy, Inc., Tuttlingen, Germany). Please note the successful guide wire insertion.    Device for a minimal

invasive access to the pericardial space

with thickened pericardium

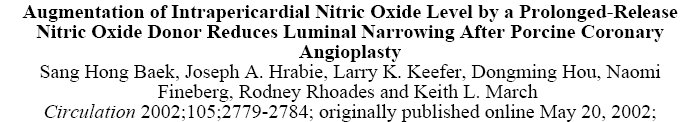

When pronounced pericardial effusion is present, the PeriAttacher could be used for draining the pericardial fluid, taking biopsies and administering drugs. Pericardial effusion can accurately be assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) (for avi file with better resolution, see Dr. Peter Alter, Heart Center Marburg) who pioneered in developing CMR-based wall stress calculation, the calculation of "isostress" curves for risk assessment and the assessment of cardiac contractility based on CMR derived presure-volume loops of the heart. A heart with pericardial effusion (right) is compared with dilative cardiomyopathy (center) and a normal heart (left). It is often assumed that a large pericardial effusion precludes the risk of puncturing the epicardium in the conventional needle approach. The CMR clearly demonstrates that this is not the case, even in a large pericardial effusion, the epicardium touches the pericardium on the front of the chest, i.e. the location where the needle is forwarded. Clearly, it depends on the skills of the cardiologist to avoid puncturing the epicardium and preventing life-threatening cardiac tamponade. In this condition, the use of the PeriAttacher and its follow-up device (not yet disclosed) would represent a safe alternative which excludes any risk of puncturing the epicardium.    © P. Alter © P. AlterIn view of recent progress in diagnostic procedures and treatment options involving the intrapericardial instillation of drugs, the treatment would have already been extended to moderate pericardial effusions if a suitable device had been available. The number of procedures with pericardial access is expected to increase markedly after the PeriAttacher and its follow-up device becomes available. The access to a normal pericardial sac without effusion would also provide a greatly unexplored approach for drug treatment of diseased hearts using intrapericardial bolus instillation. Interventions could involve instillation of drugs into the pericardial space for the treatment of inflammatory heart disease (myocarditis) in high local dose with little systemic side effects. Of great interest would be also the administration of nitric oxide (NO) donors before or after PCTA. From S.H. Baek et al.: "Perivascular exposure of coronary arteries to NO via intrapericardial D-BSA administration reduced flow-restricting lesion development after angioplasty in pigs without causing significant systemic effects. The data suggest that intrapericardial delivery of NO donors for which NO release rates and pericardial residence times are matched and optimized might be a beneficial adjunct to coronary angioplasty." Also anti-arrhythmogenic compounds (e.g. long-chain omega-3 fatty acids) could be administered shortly after myocardial infarction, however, again this requires further research. It can also be envisaged that the procedures for epicardial ablation could be improved by the present devices. The potential applications of devices using a controlled attachment to tissues or organs with subsequent manipulation procedures are manifold. Since these devices have been developed by cardiologists, the focus is currently on cardiovascular applications, in particular access to the pericardial sac. This does, however, not imply that applications beyond the cardiovascular system could not be of great relevance (therefore also the general name "Marburg Attacher"). Rather, they have just not been explored in detail. For example, it has recently been suggested that the controlled tissue attachment of our devices could be very useful for removing cysts from the uterus or the gastrointestinal tract. Are there also other routes to the pericardial space? Our devices have also to be seen in the context of the recent approach by S.R. Mickelsen et al. "Transvenous Access to the Pericardial Space: A Novel Approach to Epicardial Lead Implantation for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy" involving a transvenous access to the pericardial space which, however, is associated with acute pericardial effusion during the implantation procedure: "Background: Percutaneous

access

to the pericardial space (PS) may be useful

for a number of

therapeutic modalities including implantation

of epicardial pacing

leads. We have developed a catheter-based

transvenous method to access

the PS for implanting chronic medical

devices.Methods: In

eight pigs, a transseptal Mullins sheath and

Brockenbrough needle were

introduced into the right atrium (RA) from the

jugular vein under

fluoroscopic guidance. The PS was entered

through a controlled puncture

of the terminal anterior superior vena cava

(SVC) (n = 7) or right

atrial appendage (n = 1). A guidewire was

advanced through the

transseptal sheath, which was then removed

leaving the wire in PS. The

guidewire was used to direct both passive and

active fixation pacing

leads into the PS. Pacing was attempted and

lead position was confirmed

by cine fluoroscopy. Animals were sacrificed

acutely and at 2 and 6

weeks. Results:

All

animals survived

the procedure. Pericardial effusion (PE) during

the procedure was

hemodynamically significant in four of the eight

animals. At necropsy,

lead exit sites appeared to heal without

complication at 2 and 6 weeks.

Volume of pericardial fluid was 10.8 ± 6.2 mL

and appeared

normal in four of the six chronic animals.

Moderate fibrinous

deposition was observed in two animals, which

had exhibited significant

over-procedural PE. Conclusions:

Access to the PS

via

a transvenous approach is feasible. Pacing

leads can be negotiated into

this region. The puncture site heals with the

lead in place. Further

development should focus on eliminating PE and

performing this

technique in appropriate heart failure models.

Copyright H. Rupp is the owner of all content of this web site. The commercial use or publication of all or parts of the contents of this web site are forbidden in any form without the prior written permission of H. Rupp. © H. Rupp Impressum: Dr. H. Rupp Professor of Physiology Experimental Cardiology Laboratory Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology Heart Center, Philipps University of Marburg Baldingerstrasse 1, 35043 Marburg, Germany Tel. +49 6421 586 2775 August 23, 2013 |

The

AttachLifter and related tools have been

developed at the Department of

Internal Medicine and Cardiology of the Heart

Center and the Technical

Development Plant of the Medical Center and

Medical Faculty of

the Philipps

University

of Marburg, Office for

Research

and Technology Transfer

The team involved in the production of the Marburg Attacher and follow-up devices: Prof. Dr. Heinz Rupp Prof. Dr. Bernhard Maisch Dr. Thomas P. Rupp, M.D. Karin Rupp Michael Koch Ekkehard Schüler Hermann Schön Patent application and marketing is in cooperation with TransMIT (for the Transfer Center of the Philipps University)

For technical information on the AttachLifter, please contact Prof. Dr. Heinz Rupp For information on the pending patents of the AttachLifter and follow-up devices, please contact Dr. Peter Stumpf, Managing Director, TransMit or Heinz Rupp. For information on live demonstration of the AttachLifter and follow-up device in the pig, please contact Dr. Thomas P. Rupp, M.D. Prof. Maisch is the chairperson of "The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology": Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases Executive Summary. Advantages over currently available products. 1. truely minimal invasive access to the pericardial space. 2. No competing device available that works for thickened pericardium. 5. Pioneering technology with prospects of future intrapericardial therapy interventions. Clinical

advantages. The

procedures

minimize the risk of life-threatening cardiac

tamponade and permit also

access to the normal pericardial space.

The Attacher/AttachLifter represent an entirely new procedure with no current competition. Extensive experience has been accumulated with respect to the conventional access to the pericardial sac using a needle. This requires, however, pericardial effusion which clearly separates the epicardium from the pericardium and thus prevents puncture of the myocardium leading to life threatening cardiac tamponade. The needle technique is obviously not applicable to patients with normal pericardium but impaired heart function. This has been stated by Prof. B. Maisch: "Whilst advocating the advantages of pericardiocentesis in appropriate cases of pericarditis, Dr Maisch points out that many cardiologists are fearful of using the technique unless severe cardiac tamponade is present, a situation in which, he estimates, the volume of the effusion is at least 500 ml. He said, “At Marburg we perform pericardiocentesis in the presence of as little as 100 ml of fluid, or sometimes even 50 ml. But I would not recommend this to the ‘normal’ cardiologist, as there is a high risk of damage to the heart. But I think the subxiphoidal approach should be used more widely, because it’s safer and makes it easier to perform a full aetiological diagnosis as well as to take off fluid.” Experience has been gathered during testing of the "PerDucer" device of Comedicus Inc. which unfortunately can fail since it does e.g. not monitor the actual attachment of the pericardium before the puncturing step. The key technology is now available for accessing the pericardial space in a truely minimal invasive approach. The AttachLifter provides a solution to the critical step of tissue puncturing by monitoring tissue attachment before the puncturing step. The AttachLifter permits puncturing of thickened pericardium. Research

described here is based on limited

funding by the

Marburg

Cardiac Society and is not

sponsored by medical device

companies. Please support

the projects by a donation through the

Marburg

Cardiac Society which is a non-profit

organization. For details, please

contact

Other web sites related to the repair of diseased heart maintained by us: www.cleverfood.com www.cardiorepair.com www.carditis.com www.herzzentrum-marburg.de www.herz.online.uni-marburg.de |

For further infos: http://www.hipo-online.net